1.7.3.2 The model of core responsibility

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

Caesajanth (talk | contribs) |

Caesajanth (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

[[File:Figure 7.1 Model of Core Responsibility.jpg||frame|center]] | [[File:Figure 7.1 Model of Core Responsibility.jpg||frame|center]] | ||

</loop_figure> | </loop_figure> | ||

<br> | |||

== Internal self-attribution of core responsibility == | == Internal self-attribution of core responsibility == | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

[[File:Figure 7.3 Model of Core Responsibility.jpg|frame|center]] | [[File:Figure 7.3 Model of Core Responsibility.jpg|frame|center]] | ||

</loop_figure> | </loop_figure> | ||

== External attribution == | |||

Determining one's core responsibility and aligning one's actions accordingly is a first (systematically) necessary, but not sufficient step for a responsible and socially legitimate company. The very word "respon-sibility" refers to the intrinsic dialogical structure of the concept of responsibility.<ref><small>Cf. learning unit 5, chapter 2 [[Basic dialogue structure of responsibility]]</small></ref> The self-attribution of one's own responsibility is therefore only one side of the coin. The other side is the company's social environment. | |||

The external attribution of responsibility to a company results from its societal environment. This is because a company's environment is not a single or homogeneous actor. Rather, it is a structure of actors with plural and diverse values and demands. In a modern, [[Glossary:Pluralistic|pluralistic]] society in particular, the bilateral question-answer relationship that we have become familiar with in the basic structure of responsibility is multiplied and complicated. It is no longer a "[[Glossary:Prima Facie|prima facie]]" bilateral personal, but a [[Glossary:Multilateral|multilateral]] anonymous responsibility structure. This means that numerous and different responsibilities are ascribed to the company by actors unknown to it, such as customers, interest groups, politicians and others. They form a set of claims that, that taken together, result in the external attribution of responsibility to the company. This is shown in the right half of the figure: | |||

<loop_figure title="Plural external attribution of responsibility, authors’ translation, adapted from © IUW Berlin" id="67fbc3e30f3ac"> | |||

[[File:Fig. 7.4 Plural external attribution of responsibility.jpg|frame|center]] | |||

</loop_figure> | |||

== Balance between self-attribution and external attribution of responsibility == | |||

<loop_figure title="Scale of Core Responsibility, authors’ translation, adapted from © IUW Berlin" id="67fbc5c467347"> | |||

[[File:Fig 7.5 Scale of Core Responsibility.jpg|frame|center]] | |||

</loop_figure> | |||

Self-attribution and external attribution of responsibility take place within the social discourse. Socially virulent and controversial topics are negotiated in this discourse. | |||

<loop_area type="example">Currently (as of 2025), these virulent topics include climate change, demographic change, the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, the refugee situation and digitalization, to name just a few.</loop_area> | |||

To a certain extent, this discourse is the thematic backdrop in which companies and all of us operate at any given time and to which we (consciously or unconsciously) refer in our decisions and actions. | |||

Within this discourse, the self-attribution and external attribution of responsibility is to be balanced with each other in an argumentative manner. Different ideas about the scope, extent and limits of a company's responsibility are [[Glossary:Discursive|discursively]] ground against each other and can thus lead to a [[Glossary:Consensus|consensus]] on the company's core responsibility. As such, discourse is a structuring element of society. | |||

In an ideal sense, social discourse could be described as a non-dominated argumentative debate between the members of a society with the aim of reaching a rational consensus.<ref><small>Cf. Prechtl (1996) <cite page="107" id="67fbc5c46734c">Pr96</cite></small></ref> However, the practice in which companies act and should assume responsibility is not an ideal space in which everyone relies on the normative power of the better argument. | |||

Under the conditions of a differentiated, pluralistic society, a general consensus is even less likely than it may have been in more traditional societies in the past. It is unlikely that there is a generally accepted correctness or truth.<ref><small>Cf. Wilhelms (2017) <cite page="518" id="67fbc5c46734f">Wi17</cite></small></ref> This insight can be applied to responsibility. There will be no generally recognized scope or limit to responsibility. In this respect, the act of balancing between attributing responsibility to oneself or attributing it externally is an open-ended dynamic process that also depends on existing power relations. This also includes the fact that companies can create facts and express values with their products and services. These issues do not verbally but symbolically reflect the company's attitude and thus enter into the debate on the question of responsibility.<ref><small>Cf. Schmidt (2016) <cite page="62f" id="67fbc5c467351">Sc16</cite></small></ref> They become reference points that crystallize the perceived responsibility or – depending on the aspect – the irresponsibility of a company. Seen in this light, the creation of a dynamic balance between internal and external attributions of responsibility is also an act of negotiating the legitimacy of corporate action. | |||

<loop_area type="example"> | |||

Iron ore has been mined in Kiruna for more than 100 years, however now a rare earth deposit has been discovered. In order to exploit this deposit and because subsidence from the local iron ore mine is threatening to swallow the town, parts of Kiruna will have to be relocated. This affects about 6,000 of Kiruna’s 18,000 inhabitants. Furthermore, the indigenous Sámi population of the area fear to lose the roaming areas for their reindeer husbandry and thus to compromise their land rights. With its mining activities and future plans the government owned mining company has created facts. In a sense, it is a factual statement in the discourse on environmental and social sustainability and thus on the ethical responsibility of companies.</loop_area> | |||

<loop_area icon="IconVideo.svg" icontext="Video"> | |||

[[File:Will Sweden choose money or tradition.png|center]][https://p.dw.com/p/4Q5BN Will Sweden choose money or tradition?]<br>[[File:c7.3.2.3_web_a.png|right|100px]]Deutsche Welle - dw.com (2023, April 22)<br><br><br><small>Time to watch 5m26s</small> | |||

</loop_area> | |||

<loop_area type="websource"> | |||

[[File:c7.3.2.3_web_b.png|right|100px]] Rankin, Jennifer (2023, February 5). (theguardian.com).<br>[https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/feb/05/why-a-swedish-town-is-on-the-move-one-building-at-a-time-kirkuna-arctic-circle?CMP=share_btn_url Article: Why a Swedish town is on the move – one building at a time.]<br><br><small>Reading time 10 minutes</small> | |||

</loop_area> | |||

== Call on the mining industry == | |||

Access to the discourse and the opportunity to speak and be heard is a decisive prerequisite for exerting influence.<ref><small>Cf. Foucault (2007) <cite page="26" id="67fbca9e49d80">Fo07</cite></small></ref> | |||

<loop_area type="example">This is clearly illustrated by the example of the climate debate. It has long been known and scientifically substantiated that the global climate is changing. However, it was only with the student protests of the Fridays for Future movement that a broad social awareness was created that led to political attention.<ref><small>Cf. Nassehi (2020) <cite page="34" id="67fbca9e49d85">Na20</cite></small></ref></loop_area> | |||

In the mining sector a number of challenging discourses are ongoing and more can be expected in future, such as the benefits and downsides of the use of AI in mining or even question of social justice that arise from the increasing demand for minerals that are needed for electrification and the generation of renewable energies, among other.<ref><small>See [https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/729156/IPOL%20STU(2022)729156(SUM01)%20DE.pdf Europäisches Parlament (2022)]</small></ref> This is necessary in order to sound out its responsibility within the company and also for society. | |||

For the mining sector, the model of core responsibility is a call to become actively involved in the social discourse at an early stage. Thanks to its specialist expertise and direct proximity to mining technologies with their potentials and risks, the mining sector can make profound expert contributions to an otherwise abstract discourse on responsibility. The field of responsibility (and ethics) in mining is not yet advanced. This makes it all the more important for mining professionals to deal with ethical issues in a well-founded manner, to be heard in the discourse and to deal with their "own core responsibility", the core responsibility of the mining sector. | |||

A responsible approach in mining concerns us all. Collectively, it is about structuring our society responsibly and making it sustainable for the future. It is therefore up to all of us collectively to decide which standards and rules we impose on ourselves in order to limit or unleash our responsibility. "Ultimately, we are only responsible for what we are held responsible for - by others or ourselves."<ref><small>Heidbrink (2007) <cite page="182" id="67fbca9e49d88">He07</cite>, authors’ translation <loop_spoiler text="Original Quote" type="transparent">Man ist letztlich nur für das verantwortlich, für das man – durch andere oder sich selbst – verantwortlich gemacht wird.</loop_spoiler></small></ref> From the perspective of core responsibility, this applies equally to companies, to areas within the company (e.g. the operations department of a mining company), and to society as a whole in its plurality and diversity. | |||

Latest revision as of 15:43, 13 November 2025

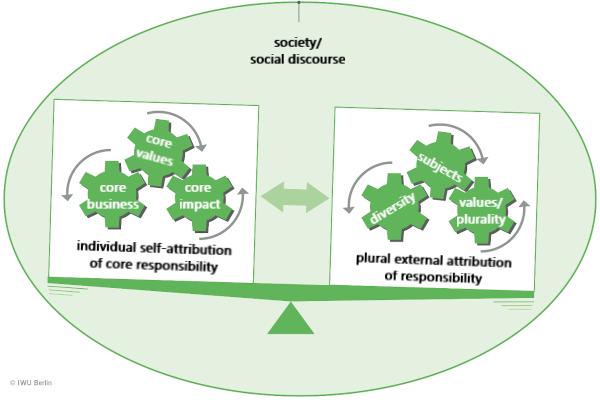

The model of core responsibility takes both an internal (a.) and an external (b.) perspective on the company. In addition, it balances (c.) its responsibility between the resulting self-attributions and external attributions.

Internal self-attribution of core responsibility

1) Core business

A first central and obvious point of reference for determining the responsibility of a company is its core business. What is the mission of the company? What products or services are created and what do the value creation processes look like? The procurement and sales structures are also functionally linked to the core business, along with the use of resources required for the provision of services.

It is easy to see that globally operating mining companies with multiple exploration sites, for example, have a different and bigger field of business than a company providing geological services to mining companies or suppliers of mining equipment.

It is therefore necessary to ask which ethically relevant and possibly critical aspects are at or near the core of the business and which are further away on the periphery of the business.

2) Core impact

A second key point of reference for the responsibility of a company lies in its core impact: Where and how does the company, through its activities or even its mere existence, have an impact in areas that cannot be described as its core business?

Consider the supply of raw materials from a company that pursues mining extraction for the processing industries.

3) Core values

Thirdly and finally, but no less relevant, are the core values that are inherent to the company. These values do not necessarily have to be explicitly stated by management; they often operate beneath the surface as informal norms. Knowing and naming the values that you consider important in general and in your business practice and according to which you act consistently would however be ideal in a theoretical sense. Core values are of great importance. After all, the legitimisation of business activities vis-à-vis oneself and others is closely linked to one's own values. The decision whether to operate in sectors that many people consider immoral or at least questionable, for example, shows the importance of values.

Whether or not you consider a core business in the arms, tobacco or sex industry to be ethically legitimate is a question of values. And the question of whether, in the mining industry, one just adheres to the legal requirements of the country in which one does business, or whether one exercises a self-commitment that goes beyond this, is also a question of the ethical values on which this behaviour is based.

In their interplay, the core business, the core impact and the core values result in the core responsibility of a company. The core responsibility modelled in this way is characterised from the previous considerations as an individual self-attribution of the company. It is initially its business, its impact and its values that the company uses to determine its own specific responsibility. This is shown in the left half of the following figure.

External attribution

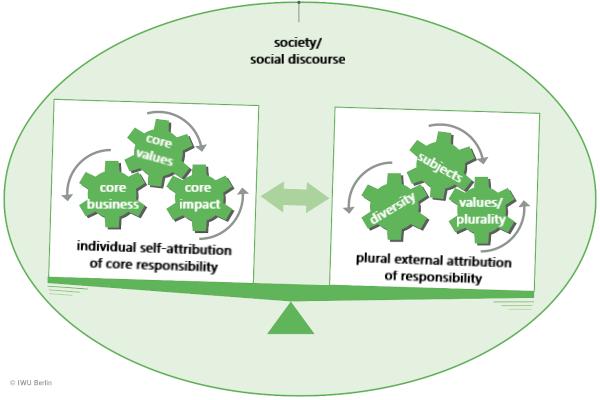

Determining one's core responsibility and aligning one's actions accordingly is a first (systematically) necessary, but not sufficient step for a responsible and socially legitimate company. The very word "respon-sibility" refers to the intrinsic dialogical structure of the concept of responsibility.[1] The self-attribution of one's own responsibility is therefore only one side of the coin. The other side is the company's social environment.

The external attribution of responsibility to a company results from its societal environment. This is because a company's environment is not a single or homogeneous actor. Rather, it is a structure of actors with plural and diverse values and demands. In a modern, pluralistic society in particular, the bilateral question-answer relationship that we have become familiar with in the basic structure of responsibility is multiplied and complicated. It is no longer a "prima facie" bilateral personal, but a multilateral anonymous responsibility structure. This means that numerous and different responsibilities are ascribed to the company by actors unknown to it, such as customers, interest groups, politicians and others. They form a set of claims that, that taken together, result in the external attribution of responsibility to the company. This is shown in the right half of the figure:

Balance between self-attribution and external attribution of responsibility

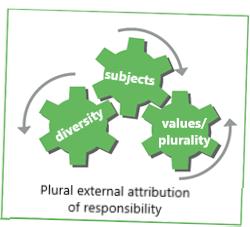

Self-attribution and external attribution of responsibility take place within the social discourse. Socially virulent and controversial topics are negotiated in this discourse.

Currently (as of 2025), these virulent topics include climate change, demographic change, the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, the refugee situation and digitalization, to name just a few.

To a certain extent, this discourse is the thematic backdrop in which companies and all of us operate at any given time and to which we (consciously or unconsciously) refer in our decisions and actions.

Within this discourse, the self-attribution and external attribution of responsibility is to be balanced with each other in an argumentative manner. Different ideas about the scope, extent and limits of a company's responsibility are discursively ground against each other and can thus lead to a consensus on the company's core responsibility. As such, discourse is a structuring element of society.

In an ideal sense, social discourse could be described as a non-dominated argumentative debate between the members of a society with the aim of reaching a rational consensus.[2] However, the practice in which companies act and should assume responsibility is not an ideal space in which everyone relies on the normative power of the better argument.

Under the conditions of a differentiated, pluralistic society, a general consensus is even less likely than it may have been in more traditional societies in the past. It is unlikely that there is a generally accepted correctness or truth.[3] This insight can be applied to responsibility. There will be no generally recognized scope or limit to responsibility. In this respect, the act of balancing between attributing responsibility to oneself or attributing it externally is an open-ended dynamic process that also depends on existing power relations. This also includes the fact that companies can create facts and express values with their products and services. These issues do not verbally but symbolically reflect the company's attitude and thus enter into the debate on the question of responsibility.[4] They become reference points that crystallize the perceived responsibility or – depending on the aspect – the irresponsibility of a company. Seen in this light, the creation of a dynamic balance between internal and external attributions of responsibility is also an act of negotiating the legitimacy of corporate action.

Iron ore has been mined in Kiruna for more than 100 years, however now a rare earth deposit has been discovered. In order to exploit this deposit and because subsidence from the local iron ore mine is threatening to swallow the town, parts of Kiruna will have to be relocated. This affects about 6,000 of Kiruna’s 18,000 inhabitants. Furthermore, the indigenous Sámi population of the area fear to lose the roaming areas for their reindeer husbandry and thus to compromise their land rights. With its mining activities and future plans the government owned mining company has created facts. In a sense, it is a factual statement in the discourse on environmental and social sustainability and thus on the ethical responsibility of companies.

Rankin, Jennifer (2023, February 5). (theguardian.com).

Article: Why a Swedish town is on the move – one building at a time.

Reading time 10 minutes

Call on the mining industry

Access to the discourse and the opportunity to speak and be heard is a decisive prerequisite for exerting influence.[5]

This is clearly illustrated by the example of the climate debate. It has long been known and scientifically substantiated that the global climate is changing. However, it was only with the student protests of the Fridays for Future movement that a broad social awareness was created that led to political attention.[6]

In the mining sector a number of challenging discourses are ongoing and more can be expected in future, such as the benefits and downsides of the use of AI in mining or even question of social justice that arise from the increasing demand for minerals that are needed for electrification and the generation of renewable energies, among other.[7] This is necessary in order to sound out its responsibility within the company and also for society.

For the mining sector, the model of core responsibility is a call to become actively involved in the social discourse at an early stage. Thanks to its specialist expertise and direct proximity to mining technologies with their potentials and risks, the mining sector can make profound expert contributions to an otherwise abstract discourse on responsibility. The field of responsibility (and ethics) in mining is not yet advanced. This makes it all the more important for mining professionals to deal with ethical issues in a well-founded manner, to be heard in the discourse and to deal with their "own core responsibility", the core responsibility of the mining sector.

A responsible approach in mining concerns us all. Collectively, it is about structuring our society responsibly and making it sustainable for the future. It is therefore up to all of us collectively to decide which standards and rules we impose on ourselves in order to limit or unleash our responsibility. "Ultimately, we are only responsible for what we are held responsible for - by others or ourselves."[8] From the perspective of core responsibility, this applies equally to companies, to areas within the company (e.g. the operations department of a mining company), and to society as a whole in its plurality and diversity.

- ↑ Cf. learning unit 5, chapter 2 Basic dialogue structure of responsibility

- ↑ Cf. Prechtl (1996) Pr96, p. 107

- ↑ Cf. Wilhelms (2017) Wi17, p. 518

- ↑ Cf. Schmidt (2016) Sc16, p. 62f

- ↑ Cf. Foucault (2007) Fo07, p. 26

- ↑ Cf. Nassehi (2020) Na20, p. 34

- ↑ See Europäisches Parlament (2022)

- ↑ Heidbrink (2007) He07, p. 182, authors’ translation

Bernd G. Lottermoser /

Matthias Schmidt (Ed.)

with contributions of

Anna S. Hüncke, Nina Küpper and Sören E. Schuster

Publisher: UVG-Verlag

Year of first publication: 2024 (Work In Progress)

ISBN: 978-3-948709-26-6

Licence: Ethics in Mining Copyright © 2024 by Bernd G. Lottermoser/Matthias Schmidt is licensed under Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Deed, except where otherwise noted.

Further Informationen:

Project "Ethics in Mining"