1.8.2 Sustainability concepts

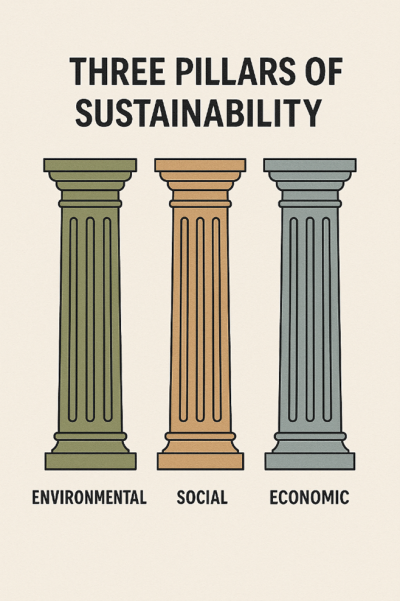

The three pillars of sustainability

The conceptualisation of sustainability as ‘three pillars’ – ecological, economic, and social – has gained widespread recognition. The pillars are regarded as balancing force between equally desirable goals within these three categorisations.

However, the three-pillar concept is not universal, as some authors add institutional, cultural, or technical pillars.[1]. This goes hand in hand with the criticism that in the dominant three pillar model economy is presented as a separate pillar, whereas culture and politics are not.[2]

The three overlapping circles of sustainability

Following this concept, the areas of ecology, social affairs and economy are located in circular dimensions that partly overlap each other. Only at the centre of the intersections sustainable development is fully achieved. Thus, it cannot be achieved if the focus is only on one or two of the dimensions. In fact, sustainable development can only be achieved if all dimensions work together.[3]

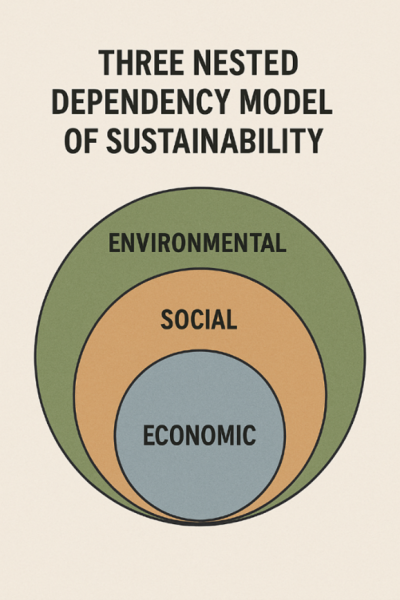

The three nested dependency model of sustainability

According to this integrative model, an intact ecology forms the basis for a functioning society. The model sees economy as a subsidiary of society, and society as a subsidiary of the environment. Thus, the concept of "nested dependency (…) illustrates the co-dependent relationship within the social and economic spheres and the governing role the environment enjoys in sustaining the human subsystems".[4]

Further reading:

University of Waterloo (n.d.).

Ways of framing sustainability.

Further reading:

Willard, Bob (2010, July 20).

3 Sustainability Models.

Sustainability Advantage.

Compare the nested dependency model and the three pillars model and elaborate on the following question:

Why does the economy receive a relative upgrade in comparison to the environment in the three pillars and how does this differ from the relation between economy and environment in the nested dependency model?

Time to complete approx. 30 min.

Weak and strong sustainability

Weak sustainability

The concept of weak sustainability assumes that natural capital can be substituted with human-made capital, such as technology or infrastructure, so that the overall capital stock can be maintained for future generations. The approach follows the principle of “non-declining utility over time”.[5] Focusing on economic growth and human welfare, it allows for trade-offs between environmental degradation and development as long as total capital remains constant. This relies on the belief that technological advancements can mitigate natural resource depletion or environmental harm. In contrast, critics argue that the concept underestimates the unique value of natural systems and therefore often link it to mainstream economic models (such as neoclassical approaches) prioritising short-term gains. Unlike, for instance, the above mentioned three pillars model which emphasises equitable integration of all three dimensions, weak sustainability allows for trade-offs that can undermine ecological integrity.

Strong sustainability

The concept of strong sustainability emphasises the unique value of natural capital, asserting that human-made capital cannot fully substitute for ecosystem services and natural resources. It prioritises the preservation of critical natural systems, like biodiversity and climate systems, for future generations, viewing them as irreplaceable. Consequently, economic activities have to operate within ecological limits, avoiding depletion or degradation of natural systems. The approach advocates for systemic changes to reduce resource extraction and pollution and thus does not necessarily follow an anthropocentric concept but rather assigns a moral value to nature itself.[6]

Strong sustainability contrasts with weaker sustainability models by rejecting the idea that technology or wealth can fully compensate for environmental losses. However, also differently to the nested dependency model, which explicitly structures the three dimensions in hierarchical dependency, strong sustainability focuses on ecological limits without defining this hierarchy.

Bernd G. Lottermoser /

Matthias Schmidt (Ed.)

with contributions of

Anna S. Hüncke, Nina Küpper and Sören E. Schuster

Publisher: UVG-Verlag

Year of first publication: 2024 (Work In Progress)

ISBN: 978-3-948709-26-6

Licence: Ethics in Mining Copyright © 2024 by Bernd G. Lottermoser/Matthias Schmidt is licensed under Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Deed, except where otherwise noted.

Further Informationen:

Project "Ethics in Mining"